This is the book that I wish I’d found when I first got sick, nearly twenty years ago. Getting sick and not getting better was such a shameful and isolating experience for me ( as well as being extremely ill). This book would have banished the shame and made the isolation a little less lonely.

I love love love the dyslexic friendly layout and font. It is sooo easy to read, I almost wept. Designed with practical workshop sections, clearly outlined exercises offer practical support, ideas, and sometimes just an acknowledgement that it’s absolutely ok to feel how you feel.

About Grace.

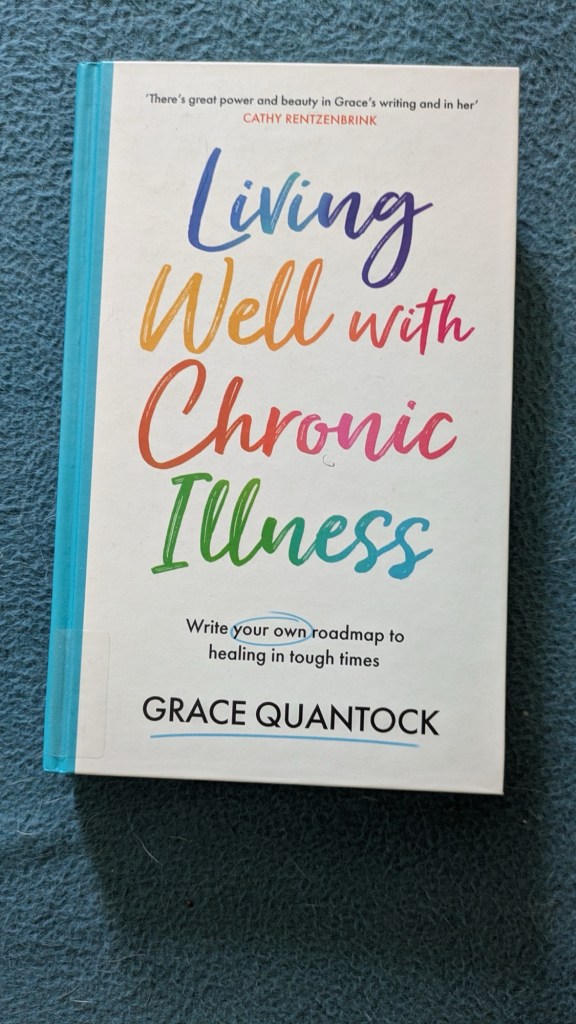

I am a UKCP-accredited psychotherapeutic counsellor and author of Living Well with Chronic Illness: Write Your Own Roadmap to Healing in Tough Times (Orion Spring, 2024). My writing, spanning both fiction and non-fiction, explores collective trauma, community care, and embodiment. My work has appeared in The Guardian, The New Statesman, and A Woman’s Wales and An Open Door (Parthian). I’ve received recognition through awards including The London Library Emerging Writers Award, Writers and Artists Working Class Writers Award, Curtis Brown Creative Breakthrough Award and A Writing Chance. With a background in history and training spanning writing, somatic, therapeutic work, I help marginalised folks navigate pain, illness, and trauma.

Can you tell us a little about the book?

My book Living Well With Chronic Illness is a practical guide for navigating life with chronic illness and pain, in these times It’s not about miracle cures or positive thinking platitudes—it’s about finding pragmatic ways to live well within the realities of our bodies and the systems we must navigate. The book combines therapeutic approaches, practical exercises, and insights from disability justice to help readers advocate for their needs while supporting their energy and wellbeing. I’ve designed it to be accessible, with dyslexia-friendly formatting and clear, compassionate language that acknowledges the full complexity of living in bodies society often fails to accommodate.

Where did the inspiration for this book come from?

It started for me, like for many of us, with illness.

I became seriously ill at 18 when my underlying auto-immune condition relapsed. I was thrown into a world of illness, of hospital waiting rooms, too few answers and too many blood draws. I brought my experiences from activism and academia to the task – experience had taught me with research and strategy, I could effect change.

As I learned how to navigate the struggling and systemically unjust systems, I learned just how difficult making change would be. But through learning from other sick folks on message boards, in waiting rooms, and while queuing for accessible bathrooms, I learned how to navigate this new world. I drew on my academic background to research – we called it going to Healing University.

Somehow, word spread, and my phone became an informal crisis hotline… How did you get that equipment from an occupational therapist? Someone was being denied medical treatment? An institution was refusing to make access adjustments? My friend has been moved into a care home against their will and they’re scared, what can we do? We called it Grace’s Crisis Hotline and calls came in at all hours. I began to realise the problem was bigger than I had ever imagined. But I didn’t know what I could do.

One day, a chronically ill friend was visiting and I showed her my Healing University research folder (complete with colour-coded paper clips and reward stickers for completing tasks). I thought it was a sweet topic to show my love of stationery.

But she was furious.

She asked me why I had not shared this research and these resources. “How dare you?” she challenged me. “Don’t you think someone like me could benefit from this?”

I was stunned, but I saw her point.

“We aren’t all like you, Grace,” she went on. “You have an academic background, you got to go to university. When you ring experts up to interview them, they speak to you. Why don’t you share this?”

I agreed I would, but I had no idea what that could look like. The next month, when I was 22 years old, my doctors told me they suspected I had extensive bone cancer throughout my body.

I didn’t know if I could cope with chemo. Who does? It’s not something any of us can choose.

On the day I was due to get the results, I came out of hydrotherapy and waited for the call under a beech tree on the grounds. I started to make a list on my phone of what I needed to do if I didn’t have to dedicate my energy to chemo and ensuring survival. Living bigger felt impossible when most days I struggled to take my pills and eat. But I wanted to be able to move forward, alongside my fear. I realised my life needed meaning beyond a focus on my survival.

I made my list:

- I want to wear more earrings and dare to have a style beyond ‘looking disabled’ and wearing the most accessible clothes.

- I want to camp in the Forest of Dean and see the stars again.

- I want to share all we’ve learned in Healing University with others.

I got the call that I had severe osteoporosis (not cancer).

I spent the next six months researching bone-strengthening treatments and fighting to get permission to work without losing my benefits. When permission came through, I sent my friends and family an email entitled “I’m Legal, Celebrate With Me”. I asked them to recommend my coaching sessions to people they knew who were struggling with illness.

My coaching sessions and seminars got booked out over a year in advance. My Healing University research and Grace’s Crisis Hotline work became a blog, a business, a viral TEDx talk, a thriving coaching/mentoring practice and later, after years of training, psychotherapeutic counselling practice.

I’m still sick, still not cured, but I found more possibility and space to live when I stopped trying to have a life designed by someone else, for bodies not like mine.

But my work is not about teaching you my path or trying to make you like me. I intimately understand that the charity model of disability doesn’t work. Not only is it patronising – I don’t need pity – but it’s inaccurate as for most of us, we aren’t a singular sick person surrounded by well-resourced non-disabled people with plentiful time, money and energy to support us and our goals.

We heal in community and we may be both responsible for/to others and living in relationship with people, communities, landscapes and lineages. This means we don’t heal alone, even when we feel alone. We have to account for this when we are thinking about change.

The Bootstrap Wellness Narrative tells us we can do it all ourselves if we try hard enough. I don’t think that’s what it is to be human. I’m working with you to find your own way, what fits your body and life.

Did your ideas around chronic illness change while writing the book?

They definitely developed as I immersed myself even more deeply in the writing of other disabled people like Alice Wong and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha. The process of explaining concepts that I typically teach one-on-one or in groups helped me refine them further. When you’re teaching in person, you can clarify if people are confused, but writing requires anticipating questions and being exceptionally clear from the outset.

After teaching these concepts for over a decade, I’ve learned to articulate them more precisely. Writing the book forced me to distill what I’ve learned into accessible language without losing the nuance or complexity of living with chronic illness. I found myself constantly asking, “How can I make this more useful, more honest, and more respectful of the reader’s own expertise about their body?”

Can you tell us a little about your writing practice?

I’m afraid it’s very pragmatic and unromantic. I write on Tuesdays or Fridays and make detailed plans before I begin.

When I first started working on larger projects, I began with post-it notes pinned to a throw by my PA (back when I had funding for direct payments). Today it’s part of a detailed plan. I tried using Scrivener, but my laptop was too old to run it properly and I almost lost everything, so I went back to Pages.

When I write, I imagine someone I work with or have worked with, and write as if we’re speaking. This helps keep my voice authentic and ensures I’m not using jargon or getting too academic.

When did you first start writing?

I’ve been writing as long as I can remember, but my professional writing journey began with copywriting and ghost writing in my early 20s. I also wrote one of the UK’s first chronic illness/wellness blogs. Initially, I wrote purely practical guides and resources—how to navigate benefits systems, how to prepare for medical appointments, how to advocate for yourself when you’re dismissed. As I trained in psychotherapy and deepened my understanding of trauma and systemic issues, my writing expanded to address the emotional and social dimensions of chronic illness. I hope to be a part of the growing and developing conversations about disability that aren’t rooted in inspiration porn or miracle narratives and I am grateful and honoured to get to write and to learn from the amazing activists and artists whose work I love and those creating today.

What advice would you have wanted to be given when you were an aspiring writer?

Write now, don’t wait until it’s you have everything set up. You can work towards getting the perfect set up, but by then you will have lots of practice and drafts behind you to build on. You can, but don’t have to, romanticise writing—I’ve found it helpful to make it portable and accessible.

Learn to differentiate between your creativity and your commerciality. Many people don’t like marketing or social media, but when I’m taking my writing to the public, I want to meet them where they are and make it possible for people to get hold of my work and words. That includes considering agents, acquisitions editors, marketing and sales teams, indie book reps, large bookstore buyers, and library buyers when I’m creating marketing materials.

Making your work a sellable offering can help it reach those who need it. We had to change my title from “Reclaim Your World” to “Living Well With Chronic Illness” because no one is googling “reclaim your world,” but many are searching for guidance on chronic illness.

Do you ever get feedback from readers, and what do they say?

Yes, lots! Readers express appreciation (and surprise) that the book speaks to their real-life experiences and isn’t overly aspirational, which is unusual in self help. Many appreciate that we made it dyslexia-friendly working with guidelines from the British Dyslexia Association and ran the cover through a great focus group so it has been edited to be colour-blind friendly, and visually impaired accessible as possible. The most meaningful feedback has been from people who say they finally feel seen and understood, rather than being told to just try harder or think more positively about their conditions.

Did you have a favourite book as a child?

Yes, but probably too many to count! I also loved audiobooks and have favourite narrators, I think Martin Jarvis was probably my favourite narrator as a child.

What are you reading?

I’m currently reading “Loving Our Own Bones” by Julia Watts Belser and “The Serviceberry” by Robin Wall Kimmerer. I’m also enjoying “Drop Dead” by Lily Chu on audio.

Are you a member of your local Library?

Yes, I’m a member of Torfaen Library. Libraries are vital community resources, especially for those of us with limited mobility or energy. They provide not just books but connection, information, and a space that doesn’t require purchasing something to exist within it. I’ve benefited from the Library At Home service who selected and dropped off books when I am too sick to attend the library. And as a household, we have a Carer’s Card, so we don’t get any fines if either of us are unable to return books due to caring responsibilities.

What are you working on now?

I’m currently writing about collective care and mutual aid for chronically ill and disabled communities. I am also scheduling workshops on Creative Therapeutic Journalling, which helps people process their experiences through accessible creative practices. And my weekly newsletter, Healing in Tough Times newsletter is where I’m expanding my work on how folks can navigate healthcare systems without burning out or internalising blame. With the increasing pressure on the NHS and social care, I’m focusing on how we can support each other when systems are struggling, while still advocating for the structural changes we desperately need.

What question do you wish you’d been asked and what would be the answer?

I’d be delighted to answer, “How can non-disabled people meaningfully support disability justice without taking over or centring themselves?”

The answer is to start by listening to disabled people—not just the most visible or palatable ones, but those with complex and multiply marginalised identities. Support our work financially where possible; pay for our books, workshops, and consultancy rather than expecting free education. Make your events and spaces accessible from the beginning, not as an afterthought. Challenge ableism when you see it, especially when no disabled people are in the room. Understand that access is about belonging, not just being able to get through the door.

Most importantly, recognise that disability justice isn’t just about individual accommodations—it’s about transforming systems that were built on the assumption of a particular kind of body and mind. It’s about questioning productivity as the measure of human worth. It’s about recognising that interdependence, not independence, is the reality of human existence. When you advocate alongside disabled people, you’re not just helping us—you’re helping create a world that will better accommodate all of us as we age, get sick, experience injury, or simply live in bodies that change over time.

Wishing you good days & good things,